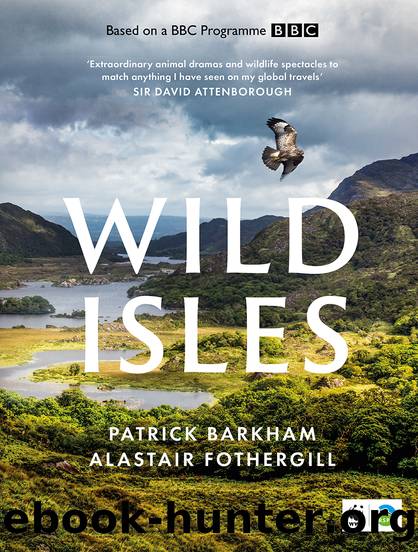

Wild Isles by Patrick Barkham

Author:Patrick Barkham

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Each winter, thousands of knot gather on the Wash, one of Britainâs largest estuaries. When the tide comes in, numbers become even more concentrated on the low banks.

© Nick Gates

The Wash is full of bird species in winter because the daily tides expose vast mud and sand flats rich with intertidal life â a precious and reliable food source.

© Craig Denford

As autumn turns into winter, huge numbers of knot flock on the Wash, more than anywhere else in Britain. In the winter of 2020/21, there were 220,000 birds gathered on the mighty estuary. And on a high tide, as the mudflats are covered, the birds are squeezed together, packed tighter and tighter. It is here that the birds rise up, in great shimmering flocks, like a murmuration of starlings only mightier, with much bigger birds.

Britain has clung on to precious fragments of its special wildlife but rarely do we encounter abundance in our nature-depleted land. But an uplifting mass of life is here on the Wash in winter.

RSPB Snettisham is a large nature reserve on the southeastern corner of the Wash. It can appear a bleak, barren place but it provides a safe haven for overwintering birds. From late November to January, alongside more than 100,000 knot that gather on this one portion of the Wash, there may be up to 50,000 pink-footed geese roosting here at night, flitting between this reserve and similarly protected places on the North Norfolk coast at Holkham and Scolt Head Island. Alongside the geese and the knot there can be up to 4,000 bar-tailed godwits, 7,000 oystercatchers and 5,000 dunlin.

We know this because Jim Scott, the RSPB warden here for more than 20 years, conducts an arduous monthly count during winter. Even a rare and declining bird such as the curlew may gather in its hundreds here. Of a grand total of nearly half-a-million wading birds in the Wash, a third of them are usually mucking about at Snettisham, picking through the mud in their search for precious winter food.

It is uplifting to experience so many birds. Their calls echo through this grand arena, and when the incoming tide causes a group to lift up, the air is filled with the swish of thousands of wingbeats, sounding like a mighty engine. But other animals are attracted to such a bounty of life too: predators.

When the high tide crowds the knot onto a small area of mudflat, they are vulnerable. And a peregrine knows it.

A peregrine will launch a surprise attack on a flock of knot. It approaches by flying low, fast and hard, more like a female sparrowhawk than a peregrine, using the ground to conceal its approach. By the time the first group of knot take to the skies in alarm, the peregrine is almost upon them. There are so many birds it can usually grab one in midair.

The knot scatter, a mass of silver-grey shapes rising in panic, each one twisting and turning to evade their mortal enemy. There is safety in numbers but when a knot knows it is being targeted it will do almost anything to escape.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4786)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4443)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4294)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3938)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3808)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3677)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3603)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(3448)

Hedgerow by John Wright(3340)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(3315)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(3296)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(3287)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3207)

Origin Story by David Christian(3184)

Water by Ian Miller(3166)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(3053)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2914)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2846)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2823)